Work With Your Hands And Think On Your Feet,

There is always at least one part of a build that blindsides me. Whether I'm working from detailed scaled plans I painstakingly drew myself or a scratched rough sketch on the small chalkboard I keep by the bench, there is always at least one thing I failed to foresee. I understand that's why many prototype important pieces and I could do that. You'd think I'd do that since I'm dealing with such a precious and finite resource as the stock from these two walnut boards.

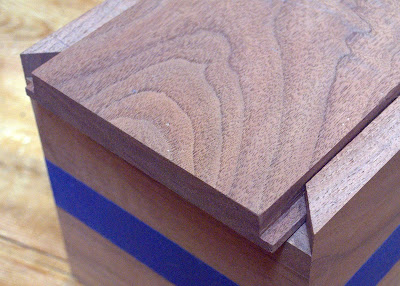

I'm much more of a two-foot-in kind of person and problems like the one pictured above are actually the challenges I appreciate. I had the miters planned, the sliding rabeted "pencil box" style lid planned, but I missed visualizing where the two would meet. Once I got this far I stopped and cleaned the shop. It helps me think.

I thought about several solutions. Rounding over the points on the miters and saying good enough. This was not the project to take a short cut and say those two words. (I hate those two words) I considered scabbing in little mitered and slotted pieces to fill the gap and bring the sides of the box out even with the end and that was a promising thought, but getting the grain to match and the pieces to hold in alignment in clamps and blah blah blah. It was too complex of a solution.

I'm not sure if this is a common solution to the problem. I don't remember seeing it addressed in magazine or book before but I can't be the first to enact such an explication. It starts with marking and squaring off the offending miter points.

Then using an offcut, creating a tongue and groove joint at the end of the lid.

The tongue board end will be secured with wedged pegs and all will be copacetic again. But there's one more lesson in this piece.

I cut the end piece long for several reasons. Protecting myself from blow out and giving myself a larger reference surface to work from are two important ones, but a side effect is it allows me to slide the piece to fine tune the best visual impact. Early on in my on-going woodworking education I remember watching a video by Charles Neil where he discussed the many ways to consider the grain and it's visual impact in your work.

You can see how the grain lines flow from the panel into the end piece even though they're cross grain to each other. That's a recipe 40% serendipity and 55% paying attention and planning and 5% work.

He blew my mind talking about how in super high end furniture the grain of the stiles and rails (in floating panel doors) should not only flow around the corners, but how the face frame of the cabinet behind the door should be cut from the same boards as the rails and stiles so the grain continues to match as you move visually deeper into the piece. The consideration of the material and it's effect on the details in a work was a paradigm shift for me.

It almost made me quit woodworking. I was sure I'd never be able to work at that level, but once you know about it you start seeing it. Once you start seeing it YOU CAN'T STOP. It's like looking for clocked screws. It is the number one issue that bothers me when I see higher quality manufactured furniture. The thing is, it's not as hard to carry through on as it sounds at first.

The trick I've found is just to be mindful of the concept as you're moving through your wood selection and making your choices. There's a line between being wasteful in slavish obedience to matching grain, and being conscious of how the grain works throughout a piece and aware that while you might be the only person to ever notice the way things line up there is a visual difference that someone unaware of the concept will notice, even on a subliminal level.

It's just one more step into the deep rabbit hole that is woodworking.

Ratione et Passionis

Oldwolf

People with less "independent thinking" would have slavishly followed traditional box making plans (from various books), and might, or might not, have discovered that boxes of mitered construction rarely have sliding lids. They usually have lift-off lids, or pivoting lids, avoiding the dilemma you found.

ReplyDeleteGood thinking brought you to a very fitting solution, and the grain matching works really well.

Nicely done!

I have seen at least 1 box in an antique store that used a similar solution but retained the mitres.

ReplyDeleteGerry