A Newer, Studlier Marking Gauge.

Going through some photos I found a quick project I meant to blog about several months ago but missed. Mea culpa.

Marking gauges are unquestionably an essential part of any woodworking tool kit. As ubiquitous as the square, even those who primarily prefer power tools keep one or two around. Just like the square; there are several variety of gauge that accomplish the same task, and while I appreciate rod style gauges like the Tite-Mark, I don't own a one because I adore the older style wooden gauges.

Next was making a new cutting blade. I unceremoniously dumped the old jig saw blade in the bin and rummaged around the "broken shit" drawer for a suitable replacement.

By far the pickiest part of the process was making the small wedge to hold the blade in place. The new beam of walnut was no problem to fit but I went through four different wedge attempts before I was happy.

But the detail work wasn't done there. There was chamfering the ends of the beam. Hitting everything with a dry polissoir (no wax) and then a couple coats of thinned garnet shellac.

The end result was quite pleasing. I have a pin gauge to work on yet in the same manner, but like most things I got distracted before I could start it.

|

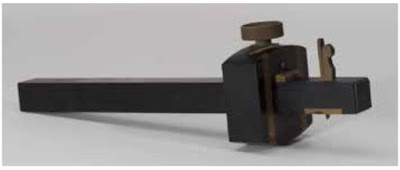

| H.O. Studley's cutting marking gauge. Image taken from the book "Virtuoso: The Tool Cabinet and Work Bench of Henry O. Studley" If you haven't bought it I don't know what you're waiting for. |

Marking gauges are unquestionably an essential part of any woodworking tool kit. As ubiquitous as the square, even those who primarily prefer power tools keep one or two around. Just like the square; there are several variety of gauge that accomplish the same task, and while I appreciate rod style gauges like the Tite-Mark, I don't own a one because I adore the older style wooden gauges.

How many gauges does one woodworker need? Surely we all keep several versions of a square around so how many do you need to keep in your tool chest? While you can get away with just one, I find four to be a nice even number for the busy woodwright. Personally I keep five in my tool chest but what's life without a little excess.

Four might seem like excess to many but hear me out. I keep two pin style gauges, this way I can keep track of two settings without changing anything. I also keep a cutting gauge with a sharp blade, and a mortising gauge. The one oddball is a double beam gauge I was given by my father-in-law. It has very fine points that exceed in fine detail and narrow settings so it's earned its place.

I find them all over the place in antique stores and second hand shops. I've never paid more that $10.

The ugly duckling of the group was the cutting gauge. It was the first beaten foster child to come into my shop while I was just starting to figure out this woodworking thing. The beam was marked as a Stanley Sweetheart but was beaten and worn and the cutting blade had been worn away to barely anything. The most salvagable piece was the head or fence.

Necessity, invention, and mothers who all drink from the same cup of cliche, I did what I knew at the time to make it usable. I cut a new beam from pine scrap and did a amateur's job of fitting it to the head's recess. Then I a hole in one end and flattened one side with a chisel. For a blade I used a broken piece of jigsaw blade. I ground and sharpened an edge on it and held it tight in the beam with a piece of dowel.

The ugly duckling of the group was the cutting gauge. It was the first beaten foster child to come into my shop while I was just starting to figure out this woodworking thing. The beam was marked as a Stanley Sweetheart but was beaten and worn and the cutting blade had been worn away to barely anything. The most salvagable piece was the head or fence.

Necessity, invention, and mothers who all drink from the same cup of cliche, I did what I knew at the time to make it usable. I cut a new beam from pine scrap and did a amateur's job of fitting it to the head's recess. Then I a hole in one end and flattened one side with a chisel. For a blade I used a broken piece of jigsaw blade. I ground and sharpened an edge on it and held it tight in the beam with a piece of dowel.

That was… oh fifteen or more years ago. And it worked . . , kind of . . . except when it didn't. Then I entered the realm of the Studley Effect.

It's better to be lucky than good, and I consider myself so. A few months back I got to spend time hanging around Don Williams and the Studley Tool Cabinet and Workbench as a docent for the Icon's exhibition which ran concurrent to Handworks. Even a little time around the chest is a life changing experience. (Much less hanging around Don and the rest of the docent crew, a really inspiring bunch of creatives) I was fortunate to spend more than a little time (though not nearly enough)

Over and over I heard people ask Don one of the big questions, "Which tool is your favorite?"

His answer…the infill mallet from the upper right till. Narayan Nayar, the book's photographer, is smitten with the oilstone box that hides behind the masonry symbols on the left middle.

It made me wonder for myself. I don't think I could pick one and I'm not entirely sure I'd pick any. Maybe the No. 9 miter plane, but that's because I have an issue with miter plane envy. I did spend a while gazing at the four ebony marking gauges that flank the infill mallet. The setting and spacing of the till is so captivating to me. A heavy portcullis gate hiding the rows of gothic arches and twisting drill bits behind, by Sunday afternoon when the crowds had thinned and were allowed to stay and look on as long as they pleased, I found my sketchbook and a seat and began to scratch some ideas centered around the till.

This increased my focus on the ebony marking gauges and the contrast they had to my embarrassment back home. I made a resolution and one of the first things I started when I returned to the shop was fix my cutting gauge problem.

This increased my focus on the ebony marking gauges and the contrast they had to my embarrassment back home. I made a resolution and one of the first things I started when I returned to the shop was fix my cutting gauge problem.

It started by making a new saddle. This piece goes between the screw and the beam and spreads out the force applied by the screw. Older gauges I find have often lost this piece as it sits loosely and falls off when the head is slid off the beam. The gauge still works but the screw starts to hammer the crap out of the beam and the head can twist on the beam more easily with the force focused on a point instead of spread out along the beam.

I had a thin sheet of brass laying around. Too thin to work in a single layer so I doubled it up and curled it back on itself. A little cold hammering and a little file work to make a couple flats and a snug fit and I had a new, workable saddle.

Next was making a new cutting blade. I unceremoniously dumped the old jig saw blade in the bin and rummaged around the "broken shit" drawer for a suitable replacement.

I happened upon a broken 1/4" chisel. Perfect! A little time at the grinder and I'd worn it down to a good thickness and length. Cut it to length and a little file work to fancy up the dull end and a little time at the sharpening station.

By far the pickiest part of the process was making the small wedge to hold the blade in place. The new beam of walnut was no problem to fit but I went through four different wedge attempts before I was happy.

But the detail work wasn't done there. There was chamfering the ends of the beam. Hitting everything with a dry polissoir (no wax) and then a couple coats of thinned garnet shellac.

The end result was quite pleasing. I have a pin gauge to work on yet in the same manner, but like most things I got distracted before I could start it.

It was a good attempt to try and work the Studley out of my system so I could dive my head back into 12th century medieval France and it helped, but once something like that gets deep under your skin there's no shaking it. I can imagine years from now, someone asking me about a design element or decision on a piece and my response will be to pause, place a thoughtful finger at my lips and then reply…

"Well, because Studley."

Hopefully that will be enough and I won't have to try and explain that. I'll probably just tell them there's a book they need to read.

Ratione et Passionis

Oldwolf

Ratione et Passionis

Oldwolf

Comments

Post a Comment