The Adventure of Design.

If you write novels, like my cousin Mark does, then your trade craft is in words, but words are not enough to carry through a great story. Your medium is words, and ink, and paper, but your skill comes in story and plot. The process is simple to explain. You have an idea for a story so you write it down. Then you rewrite it, and then you rewrite it some more, then you rewrite it again, and then, after all that, you probably need to rewrite it some more.

It can be an exacting process, trying to craft and re-craft your work into the best form possible, perfecting your plot, theme, dialogue, and words.

I see correlation to this process in woodworking, specifically when it comes to the all powerful step in the process, good design. In the end it doesn't matter how well you can cut a dovetail or how smooth you can plane a board. If your design is faulty, it can look like a second grade shop class gone wrong. (hopefully minus the glue-eating)

The problem with design is that it can be a very personal thing. There are some constants when it comes to relating furniture to the human body and it's mechanics, but the softer decisions fall more in the mixed up arena of fashion, personal taste, and a hundred other influences. All these factors may just make designing a piece on of the most daunting processes in woodworking.

The other side of the coin is fretting and worrying about your design to such detail that you end up making a meal out of a snack. You can become paralyzed and bound up in the details. inflexible and unable to move forward on to the actual piece. Frustrated when the entropy sneaks into the build process and requires a change of plans, an "off the cuff" change to the design. Starting to cut to build a piece can be an intimidating thing, You've put work into planing, put money and time into selecting the right stock, and now if you prove to be fallible, you can reduce that stock to nothing but sawdust and firewood.

I understand why a lot of people like to work from published plans, it helps relieve the fears that can come in the midst of toiling away at your own design. I like to work from published plans at times myself, but mostly in just a few circumstances. One is building a reproduction of a piece. In those instances you want to get it right and getting that information from someone who had the opportunity to measure and inspect the piece is a great way to go if you can't do it yourself.

The other reason I like to use someones published plans is because that artisan is someone I want to learn directly from. Working from someone else's plans is almost like getting a glimpse inside their heads. My wife bakes cookies as her stress relief, as a result she collects recipes and cookbooks by the armload. She has said that she can tell a lot about the cook by reading the recipe. The way they order the ingredients and the details to the directions tell her about that person as a cook. I will choose to build a project from a woodworker's plans so I can gather some similar insight, and often that teaches me more in-depth lessons than the proper dimensions of a chest of drawers.

Most of the time a piece starts as a rough idea in my head. a problem to solve, something I've admired and wanted to build for a while, or a request from a rare commission. From there I move onto my sketch book. I have a small, 6"x9" bound sketchbook that follows me around almost everywhere. I have a fine arts background so I express myself best visually, using my hands. Even in other parts of my life, if I'm trying to explain a process I end up sketching something.

In those first sketches I'm not worried about perfect proportions or sizing. I want to get the big ideas down. From there I work my way back into the details, but the sketchbook is always in the rough. I'll write down measurements but they are guesstimates. I may also work out some joinery and details and plan some of the order of the build. Basically at this point I am doing a combination of mind dumping and free writing. I work fast and try and get the ideas out on the paper as they come to mind and as I think of variations.

Often I fill somewhere between 3 and 5 pages like this. Then I work back over the sketches and write additional notes, make changes in the sketches and try and envision the piece as a whole. I know just enough about sacred geometry to be dangerous and I'll play with Pythagorean theorem and golden ratios, but never as a hard and fast rule, only as a way to help fill the holes I've left behind in the fury of the sketch.

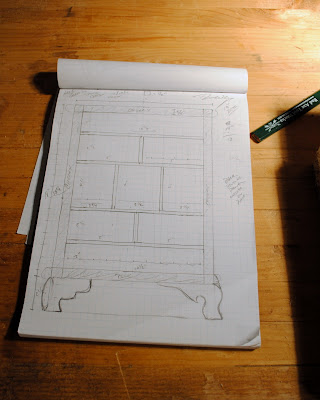

Then I'm ready for the next step, I dig out the graph paper and try to get dimensions and details nailed down tight. Here I will really focus on the measurements and the joinery details. I try to end up with a finished piece on the page.

The trick to my somewhat organic design process is that sometimes unexpected surprises happen and things take off in unprepared for directions. I have been working a lot on designing some pieces lately and something I've wanted to build for a long time is a spice chest. A small cupboard containing an apothecary of small drawers behind a showpiece door, traditionally it's an 18th century style piece.

I did quite a bit of research, both in books and magazines I own and using the net to find other examples. But I struggled with the door design. I asked my wife for some ideas, (she has a similar fine arts background) and she suggested trying to break up the door like a triptych. I liked the solution and played with size and shapes until I came up with this design.

The problem was that I liked this door a lot, but it was definitely not 18th century, it was very much Arts & Crafts style. I began to change game plan, to look at my other elements to see if they fit in with the the aesthetic the door design brought to the party. I decided the basics of the chest were safe, mouldings would have to be fit to the style, but the most difficult part was getting the feet of the case right.

You can see I played with idea after idea, some good, some crap. I tried not to judge them as I was working through them. Just put them down on paper and come back to decide later.

In the end I'm not sure if a Arts & Crafts Spice Chest is an idea that would appeal to anyone beyond me, but it is a fun exploration into the form of the chest and into the aesthetics inherent in A&C pieces, and that's really where I'm at in my learning process. Exploration.

I did get held up a little on moving forward with the build of this specific piece. One of my mother's co-workers has recently been diagnosed with a aggressive brain cancer and I wanted to build something to donate to the silent auction. Inspiration struck while I was paging through the woodworking books at my public library. I was looking at a copy of "The Essential Pine Book" (by John McGuane and Megan Fitzpatrick). Inside was a neat little desktop organizer with a couple of drawers. I decided to use it as a jumping off point for designing a similar piece in pine and cherry and donating it. After playing with the measurements, here's the scaled drawings I decided on.

The fundraiser is in February so I'll have to build the desktop organizer before the spice chest, but I'm OK with that.

Merry Christmas and Season's Greetings to you and yours.

Ratione et Passionis

Oldwolf

It can be an exacting process, trying to craft and re-craft your work into the best form possible, perfecting your plot, theme, dialogue, and words.

I see correlation to this process in woodworking, specifically when it comes to the all powerful step in the process, good design. In the end it doesn't matter how well you can cut a dovetail or how smooth you can plane a board. If your design is faulty, it can look like a second grade shop class gone wrong. (hopefully minus the glue-eating)

|

| A "car" my youngest glued together from shop scraps. |

The other side of the coin is fretting and worrying about your design to such detail that you end up making a meal out of a snack. You can become paralyzed and bound up in the details. inflexible and unable to move forward on to the actual piece. Frustrated when the entropy sneaks into the build process and requires a change of plans, an "off the cuff" change to the design. Starting to cut to build a piece can be an intimidating thing, You've put work into planing, put money and time into selecting the right stock, and now if you prove to be fallible, you can reduce that stock to nothing but sawdust and firewood.

I understand why a lot of people like to work from published plans, it helps relieve the fears that can come in the midst of toiling away at your own design. I like to work from published plans at times myself, but mostly in just a few circumstances. One is building a reproduction of a piece. In those instances you want to get it right and getting that information from someone who had the opportunity to measure and inspect the piece is a great way to go if you can't do it yourself.

The other reason I like to use someones published plans is because that artisan is someone I want to learn directly from. Working from someone else's plans is almost like getting a glimpse inside their heads. My wife bakes cookies as her stress relief, as a result she collects recipes and cookbooks by the armload. She has said that she can tell a lot about the cook by reading the recipe. The way they order the ingredients and the details to the directions tell her about that person as a cook. I will choose to build a project from a woodworker's plans so I can gather some similar insight, and often that teaches me more in-depth lessons than the proper dimensions of a chest of drawers.

Most of the time a piece starts as a rough idea in my head. a problem to solve, something I've admired and wanted to build for a while, or a request from a rare commission. From there I move onto my sketch book. I have a small, 6"x9" bound sketchbook that follows me around almost everywhere. I have a fine arts background so I express myself best visually, using my hands. Even in other parts of my life, if I'm trying to explain a process I end up sketching something.

In those first sketches I'm not worried about perfect proportions or sizing. I want to get the big ideas down. From there I work my way back into the details, but the sketchbook is always in the rough. I'll write down measurements but they are guesstimates. I may also work out some joinery and details and plan some of the order of the build. Basically at this point I am doing a combination of mind dumping and free writing. I work fast and try and get the ideas out on the paper as they come to mind and as I think of variations.

Often I fill somewhere between 3 and 5 pages like this. Then I work back over the sketches and write additional notes, make changes in the sketches and try and envision the piece as a whole. I know just enough about sacred geometry to be dangerous and I'll play with Pythagorean theorem and golden ratios, but never as a hard and fast rule, only as a way to help fill the holes I've left behind in the fury of the sketch.

Then I'm ready for the next step, I dig out the graph paper and try to get dimensions and details nailed down tight. Here I will really focus on the measurements and the joinery details. I try to end up with a finished piece on the page.

The trick to my somewhat organic design process is that sometimes unexpected surprises happen and things take off in unprepared for directions. I have been working a lot on designing some pieces lately and something I've wanted to build for a long time is a spice chest. A small cupboard containing an apothecary of small drawers behind a showpiece door, traditionally it's an 18th century style piece.

I did quite a bit of research, both in books and magazines I own and using the net to find other examples. But I struggled with the door design. I asked my wife for some ideas, (she has a similar fine arts background) and she suggested trying to break up the door like a triptych. I liked the solution and played with size and shapes until I came up with this design.

The problem was that I liked this door a lot, but it was definitely not 18th century, it was very much Arts & Crafts style. I began to change game plan, to look at my other elements to see if they fit in with the the aesthetic the door design brought to the party. I decided the basics of the chest were safe, mouldings would have to be fit to the style, but the most difficult part was getting the feet of the case right.

You can see I played with idea after idea, some good, some crap. I tried not to judge them as I was working through them. Just put them down on paper and come back to decide later.

In the end I'm not sure if a Arts & Crafts Spice Chest is an idea that would appeal to anyone beyond me, but it is a fun exploration into the form of the chest and into the aesthetics inherent in A&C pieces, and that's really where I'm at in my learning process. Exploration.

I did get held up a little on moving forward with the build of this specific piece. One of my mother's co-workers has recently been diagnosed with a aggressive brain cancer and I wanted to build something to donate to the silent auction. Inspiration struck while I was paging through the woodworking books at my public library. I was looking at a copy of "The Essential Pine Book" (by John McGuane and Megan Fitzpatrick). Inside was a neat little desktop organizer with a couple of drawers. I decided to use it as a jumping off point for designing a similar piece in pine and cherry and donating it. After playing with the measurements, here's the scaled drawings I decided on.

The fundraiser is in February so I'll have to build the desktop organizer before the spice chest, but I'm OK with that.

Merry Christmas and Season's Greetings to you and yours.

Ratione et Passionis

Oldwolf

Who cares if anybody else likes the idea? If that's what it pleases you to make, full steam ahead! At the very least, someone out there will find inspiration in some of your design elements or techniques. After all, that's really the point of all this. Get inspired, and then do it your way.

ReplyDelete